Archive: Gulf Research Blog

Blog articles from 2009 to 2012. The Gulf Research Unit is research programme based at the University of Oslo.

The Second Licensing Round in Iraq: Political Implications

Denne artikkelen er over ti år gammel og kan inneholde utdatert informasjon.

By: Reidar Visser, Researcher, The Gulf Research Unit/NUPI

The second licensing round for Iraqi oilfields was carried out by the oil ministry in Baghdad over the weekend. On the one hand, the contracts won by foreign companies will prove controversial because Iraq remains in the middle of a chaotic process of political transition and has yet to agree on a legal framework for the oil sector. At the same time, however, the relatively straightforward nature of the technical service contracts under offer as well as the emerging broader picture of a reasonably balanced mix of foreign and Iraqi participation in developing the country’s oil sector mean that these deals are on the whole less vulnerable to criticism than those previously entered into by foreign companies on extremely lucrative terms with the Kurdistan Regional Government – and therefore also stand a greater chance of surviving in their existing form in the long term.

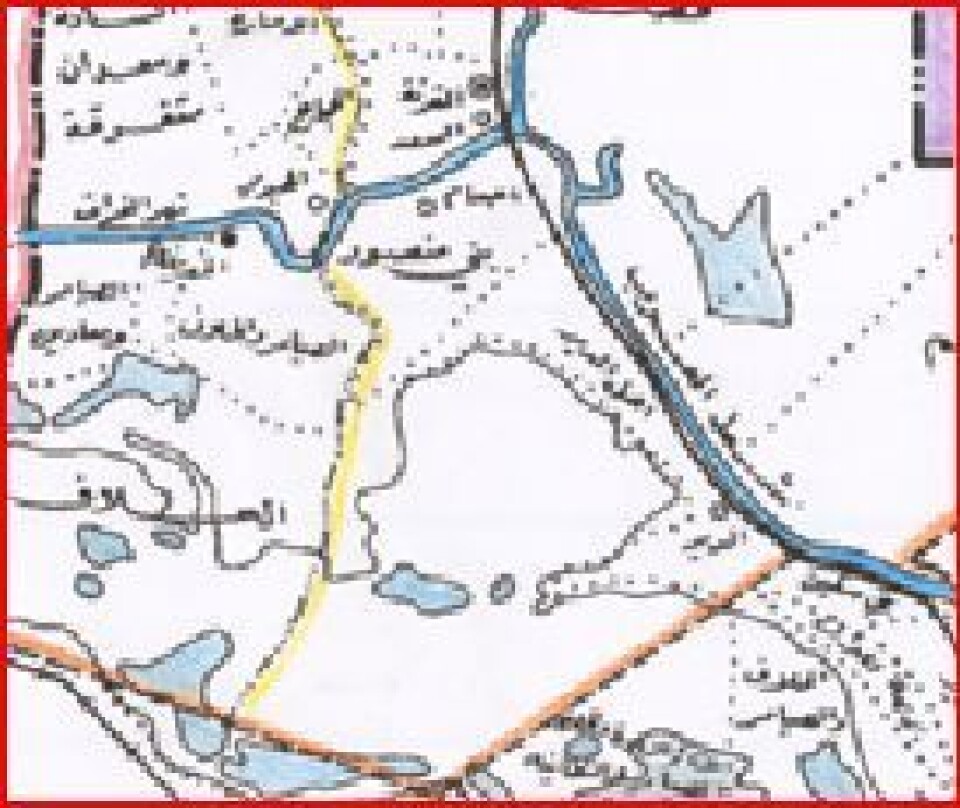

On the whole, the mostly unsuccessful first and partially successful second licensing round have ended up producing an outcome that seems more sustainable than if all the contracts on offer had been immediately awarded to foreign companies as planned. If that had happened, the whole package would have been attacked both for selling Iraqi oil on the cheap and for marginalising the domestic oil industry. In the event, a more balanced picture emerged, even if some of the failed offerings from round one (including Zubayr and West Qurna Phase 1) have since been awarded to foreign companies in separate deals (led by Italian and US firms respectively). In addition to Rumayla which was awarded to a Sino-British consortium in the first round in June, the successful bids in the second round include most notably the supergiant project West Qurna Phase 2 (in Basra; awarded to a consortium led by Russia’s Lukoil and also including Norway’s Statoil in a smaller role) and Majnun (Basra; Shell), plus Halfaya (Maysan; CNPC), Gharraf (Dhi Qar; Petronas), Badra (Kut; Gazprom) and Qayara and Najma (near Mosul, both to Sonangol of Angola). The new agreements also include partnership stakes for Iraqi state oil companies, and the “leftover” fields that were not awarded will be developed by the Iraqis themselves as well (Middle Euphrates, East Baghdad, and a group of fields near Kirkuk).

There is a narrative in the international press to the effect that this particular distribution of contracts was a result of international oil companies steering clear of “politically troublesome” areas in north and instead sticking to the “relatively stable south”. While this may perhaps come across as plausible at first glance, it is only partially correct. Karbala, for example, is arguably more loyal to the central government than Basra has ever been; however, no deals were clinched for the fields in that area. Conversely, the so-called “safe” fields in the far south are not without security complications of their own. The example of West Qurna underscores this point: The field happens to be situated in what is easily the most troublesome piece of real estate in the Basra area as far as tribal geography is concerned, with the same tribes that created problems for the British in the 1920s remaining influential on the edges of the oilfield today. In other words, the north/south distinction is likely less related to the security dimension than to the geological facts: The truly big oil potential is simply in the deep south. IOCs appear ready to take considerable risks – arguably bigger risks than those involved elsewhere – to get a foothold in this key area of Iraq.

Beyond possible security threats at the local level, the involvement of foreign companies is also potentially controversial in governorate-council politics. This is particularly the case with regard to Basra where West Qurna and Majnun are situated. Basra is home to a long-standing regionalist movement which demands improvement in living standards in an area which despite its status as Iraq’s leading oil producer still has a worse infrastructure than the rest of the country, even six years after the fall of the old regime. Last January it became clear that the vision of a standalone federal entity in Basra did not appeal to local interests; however, the decision by the Maliki government in May to set aside 50 cents from each barrel of oil exported from Basra in a separate development fund seems to testify to the continued strength of some kind of local regionalist sentiment. If the Iraqi government keeps it promise to Basra in this regard and is also able to add some jobs reserved for the local population (as has recently been attempted) then the IOCs operating in the area may well hope for frictionless conditions at the governorate level. Conversely, if opposition to the deals inside the South Oil Company should continue (this appeared to be more pronounced during the first licensing round) and jobs and development fail to materialise, then the spectre of Nigeria is not far away given the area’s political traditions.

Finally, in terms of Baghdad politics, the reception of these deals is likely to be more or less similar to the situation during the first licensing round, except that perhaps there is a greater acceptance that the fields under offer this time could be more suitable for joint development between Iraqi and foreign firms. The Kurds will remain opposed to anything that strengthens the central government, whereas Fadila may continue to oppose these deals from what seems to be an increasingly opportunistic stance aimed at hurting Maliki for failing to join the Shiite alliance for the next elections – so far at least. On the whole, though, the terms offered to the foreign companies are so modest in terms of per-barrel profit that it seems highly unlikely that any responsible parliament will opt to cancel them altogether in the future. More unclear, however, is the cumulative effect of the deals on the general direction of Maliki’s policies. The totality of the deals with very stringent and ambitious production targets mean many of Iraq’s oilfields will plateau very rapidly and hence bring lots of money to the country in a very short period of time, clearly creating an enhanced potential for corruption and autocracy (as well as disincentives for political reform) at a time when this is exactly what Iraq does not need. In this way – by pretending Iraq is normal when it isn’t – the foreign companies could help bankroll a system of government that will remain rotten at its core until the 2005 constitution has been revised.

Similarly, with respect to the Kurdistan dossier, different signals are being sent. Shahristani, the oil minister, will obviously portray the deals as a triumph that serves to emphasise the uneven distribution of oil resources in Iraq and the relative strength of the far south – and therefore will get yet another argument for continuing to ignore the Kurds until they are willing to negotiate (symptomatically, Sinopec was excluded from the second round because of its investment in Addax, which operates in Kurdistan). At the same time, though, Maliki has recently spent more time than normal talking to the Kurds. Under an alternative scenario, one could envisage that the realities of the new situation would finally encourage Kurdish leaders to break free from the maximalist position of figures like Barzani and Hawrami and instead enter serious negotiations with Baghdad. Maliki still does not seem to have made up his mind entirely with regard to potential partners after the elections, and there is no doubt that an alliance with, say, parties like PUK and/or Goran, would make more sense to him than Barzani/Hakim, not least since Maliki would then be in far a better position to maintain his centralist agenda south of Kurdistan.

In the immediate future, in terms of the next parliamentary elections now scheduled for 7 March, the net outcome of the licensing rounds is likely to be more of an asset than a liability for Maliki. He will try to sell these deals as achievements much in the way his opponents will try to sell security lapses as examples of his failure. Little wonder then that the Daawa party was among the fiercest opponents to the postponement of the elections.

See also http://gulfunit.wordpress.com and http://gulfanalysis.wordpress.com